My introduction to Grenada has been made a lot easier by a chance meeting in Maurice Bishop airport with another Scot; this time a lady from Cambuslang.

With her two friends – a Catalonian and a South African – we explored the island of Grenada in a 4×4 jeep. Along the way, the two Scots managed to stop for a photograph at Dunfermline, Grenada. The Scots eighteenth century habit of naming their estates after places back home has left an indelible legacy across the Caribbean.

In this enclosed map, the yellow line roughly represents our journey. The estate marked in green was owned in 1826 by the Glasgow firm John Campbell Senr. & Co. of Glasgow (which we didn’t visit) and the estate marked in red was owned by the ‘heirs of the Houstons’ (which we did visit). This estate, known as Belmont, had been the property of a Scot, Mr Aitcheson, before being purchased c.1780 by Robert Alexander Houston, the son of Alexander Houston of Jordanhill. Alexander Houston & Co. were the the premier sugar merchants in Glasgow, before their spectacular bankruptcy in 1801 [1]. Despite the failure of the merchant firm – essentially due to a lack of liquid capital – the Houston’s retained Belmont beyond this period.

Indeed, the Legacies of British Slaveownership project reveals that after the emancipation of slavery in 1834, Robert Houston was a large scale-claimant of compensation and was awarded £5024 for 194 slaves on Belmont Estate on 16 November 1835. Belmont estate is still in use today. However, before emancipation, sugar was the main crop and chattel slaves provided the labour.

Today cocoa is grown by wage labourers. We spent an interesting few hours finding out how cocoa is grown and harvested and the guide explained how some traditional methods have been retained. She also said she thought the Houston’s were English but I pointed out in broad Glaswegian they were Scottish! I noticed some pointers to the estates past as a sugar plantation.

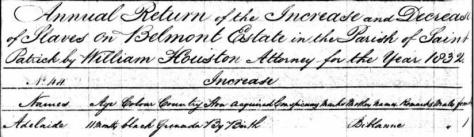

The big bell might have been rung by Scots to wake up the enslaved peoples for work at 5am whilst the large bowls (imported from Europe) would have been used to boil the juice from the sugar cane into the semi-refined muscovado – perhaps destined for the Clyde. However, there is no source detailing the lives of the enslaved people who resident on the estate. A quick search of the Ancestry website which holds digitised images of the Slave Registers, which are held the National Archives at Kew, London, illustrates this side of the story. This record shows a female baby named Adelaide was born in 1831, and was thus registered by William Houston as an ‘increase’ in the resident slave population on Belmont in 1832. As a child under six, Adelaide would have been freed automatically (as long as her mother wasn’t destitute) under the terms of the Emancipation Act 1833. However, many others like her between 1807 and 1834 would have lived, worked and died on the plantation

[1] For a good account of this see Douglas Hamilton’s ‘Scottish Trading in the Caribbean: The Rise and Fall of Houstoun & Co.’, in Ned C. Landsman (ed),Nation and Province in the First British Empire: Scotland and the Americas, 1600-1800 (Bucknell University Press, 2001), 94-126.

Hello, I read your article with great interest as my 2x great grandfather was a man by the name James Todd (born 1809) from Kirkmaiden parish, Wigtownshire, Scotland. He died at Belmont Estate, Grenada in August of 1853. We suspect that he may be buried on the estate as apparently Belmont has a cemetery. Other than that, our family does not know much about him.

Hi Brett. If you’d like more information on James Todd, and his father John Todd, get in touch via the Contact Form.

Hi Brett, I think that James Todd was in fact the son of William Todd the school master at Kirkmaiden according to the gravestone in Kirmaiden graveyard which William actually carved himself. I have a lot of information on this family and William wrote a book in which there is an excellent photograph of himself.

Thanks Jane. sorry been a while since I posted on this page. Thanks so much for replying. I also just noticed on my original post that I had stated that James was my 2nd great grandfather, this was my mistake sorry. In fact, James was my 3rd great uncle. His father, William Todd was my 3rd great grandfather. I also have a fair amount of info on the family as well and would love to share with youl. You can contact me at brettclark@shaw.ca. We also have a facebook group focussing on that particular branch among others. William Todd’s 2 great grand daughter Katy McKittrick Clachan is still alive in Scotland and holds the original manuscript of the book that you mentioned. I do have a copy of that book as well! Hoping to hear back from you!