Been a while since I blogged – I’ll return here to the Smiths of Craigend/Jordanhill and discuss now published monograph.

Archibald Smith of Jordanhill (1749-1821) was born on Craigend Estate near Strathblane (now Mugdock Park). He was later recognized by his grandson, John Guthrie Smith, the famous antiquarian, as the originator of the family West India fortune: ‘when the great West India sugar trade gained a footing in Scotland’, the family ‘took an early part in it, and prospered exceedingly…principally through the energy of a younger son, Archibald’ [1]. Archibald’s forefather, Robert Smith acquired Craigend in 1660 although it was then a small tenant farm of around 10 acres. The estate was improved in 1734 when Archibald’s father James Smith, 3rd laird of Craigend (1708-1786) extended what had previously been a minor farm holding. And improved again in 1816, when James Smith (d. 1836), 5th of Craigend, built Craigend Castle. The spectacular transformation of the Smith family into elite landowners with multiple estates coincided with Archibald Smith’s venture into colonial commerce and the involvement of family members in the West India trades across two generations

A colonial Sojourn and family West India firm

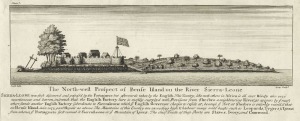

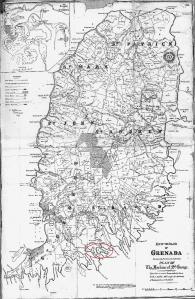

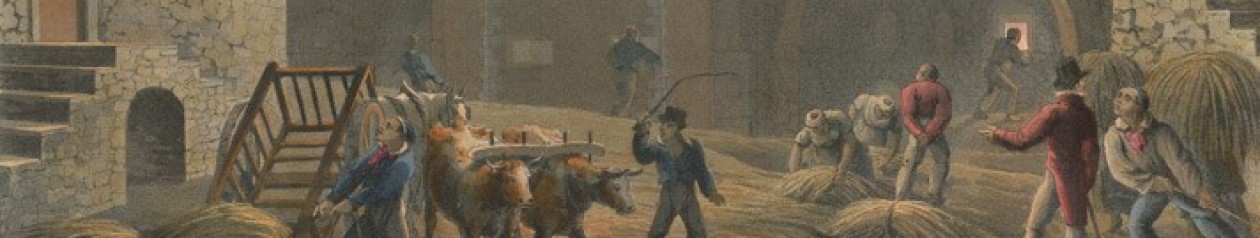

It is ironic that Archibald Smith was the source of the family wealth. As the fourth son, he was without prospects of landed inheritance and so he sojourned to colonial Virginia. Loyal to the Crown, he was expropriated during the American Revolution (1775-1783) and returned to Glasgow to establish one of the city’s major West India firms, Leitch & Smith, in 1779. The firm had a dual focus on Jamaica, the major sugar colony of the British Empire with a large population of Scots, and Grenada, subsumed into the empire in 1763 and provided increasingly large slavery-derived fortunes for Scots on the island. The firm owned land around Carenage, likely a warehouse to load produce grown by enslaved people and manufactured goods shipped from Clyde ports.

Glasgow-West India commerce

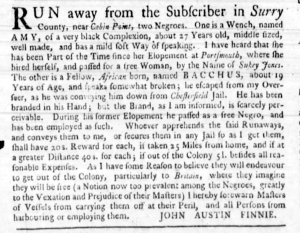

Leitch and Smith became the quintessential family firm. John Leitch, initial co-partner, died in 1805. Archibald had already introduced two of his brothers, John Smith of Craigend (1739-1816) and James Smith of Craighead (d.1815). The firm (and successor firm J&A Smith after 1824) operated a classic commission system; importing produce to the Clyde (sugar, and especially cotton), as well as manufactured goods such as textiles. Archibald Smith invested in linen production and in James Finlay & Co., the largest producer of textiles in early nineteenth-century Scotland. This was classic vertical integration, and no doubt some of these goods were shipped to Scottish planters in Grenada. Whilst there is no evidence the firm were involved in the African trafficking in a major way (historically known as the ‘slave trade’), the firm purchased enslaved people (likely for their stores in St George’s Grenada) and also extended credit to planters on the island, taking enslaved people (including children) as collateral prior to the abolition of plantation slavery in 1834. The work of genealogist James Smith on microfilms of Grenada’s deeds (the originals are held in Grenada Supreme Court Registry) underlines Leitch & Smith – whose co-partners comprised John Smith, laird of Craigend – purchased male enslaved people on Grenada in 1812,

do grant bargain sell enfeoff and confirm unto the said Archibald Smith John Smith James Smith Adam Crooks John Guthrie John Ryburn James Smith Junr Andrew Rankin and John Lindsay their Heirs and Aʃsigns _ certain Male Slaves names Louis, Alexis Brutus and Sampiere and the reversion and reversions remainder and remainders iʃsues and profits thereof and all the estate right title and interest use trust property claim made and whatsoever _ at Law or Equity of one the said Walter McInnes of unto the said Slaves to have and to hold the said Slaves named Louis Alexis Brutus and Sampiere

James Smith, ‘A Genealogy Hunt‘, Available: http://agenealogyhunt.blogspot.com/2010/02/part-207s-smith-robertson-genealogy.html

The Family Firm and the Smith’s declining fortunes

Whilst the firm was not involved with the Africa trafficking to a large extent, the enterprise was entirely dependent upon chattel slavery and the partners became enslavers themselves. The three brothers and senior co-partners – Archibald, James and John – accumulated major slavery-derived fortunes. For comparison, James Smith of Craighead’s personal wealth of £71,026 on his death in 1815 (that is moveable property only, not the value of his land/heritable property) is equivalent to £61.2m in modern values (relative to the worth of average earning in 2021) [2]. Archibald and John Smith both introduced their sons into the firm. However, as this table shows, the fortunes available to the Smith family gradually decreased, as bemoaned by John Guthrie Smith in the antiquarian text The Parish of Strathblane (1886), who noted the sale of the family seat Craigend in 1851: ‘the fortune, and for those times it was a very large one, gradually melted away till it finally disappeared’ [3].

The Smiths of Craigend Castle

John Smith of Craigend (1739 – 1816), and his son, James Smith (d.1836), were already landed, in possession of Craigend through primogeniture. But entry into West India commerce dramatically increased their personal wealth and both improved Craigend estate. On his father’s death in 1786, John Smith inherited Craigend castle and immediately rearranged farms and constructed roads. By 1800, ‘the laird having by this time become a West India proprietor, had more money to spend and built a very comfortable suitable house’. After John Smith’s death in 1816, his son James pulled down the barely two-decades-old edifice and erected Craigend castle with the tower that became known as ‘Smith’s Folly’ [4]. The castle would have served as the main Smith residence, and they might have travelled fortnightly to Glasgow (10 miles south) to take care of West India business. The Smith family scooped up land close to the family seat. In 1800, Archibald Smith purchased the estate, Jordanhill (7 miles south of Craigend). Their cousin, John Guthrie Smith, also involved with Leitch & Smith in Grenada, purchased the estate of Carbeth Guthrie c.1800. Both were also noted improvers.

Mugdock Park and Caribbean Slavery: Interpretive Silences

Craigend Castle is now a ruin, having been abandoned in the mid 20th century: the estate was designated a country park in 1987. The stables were built in 1816 alongside the castle (and so are also a legacy of Caribbean slavery) and remain intact. They currently home an arts and craft shop which attracts a lot of annual visitors. As noted in the interpretation panels, the frontage of the stables was very ornate as this would have been the first sight of the visitors as they arrived at the castle.

Craigend castle is just a short walk away from the castle, as the above map from the National Library of Scotland denotes. It is now in a ruinous state although the grandeur of the edifice conveys some of the Caribbean slavery derived opulence that the Smiths of Craigend lived in after 1816.

The provenance of the wealth of the Smiths of Craigend, and the Smiths of Jordanhill, is reasonably well-known. Yet this is hardly acknowledged on interpretation panels in Mugdock. John Smith is described as a ‘West Indies merchant’ yet what this entailed, as described above, remains untold.

The Mugdock park website deploys similar euphemisims, claiming that the ‘Smiths had prospered greatly having acquired property in the West Indies’ and that the ‘Castle reflected the Smith’s recently acquired wealth’. It could also state that Craigend estate was one of the premier examples how a family’s wealth was improved via Caribbean slavery and this in turn underlines the influence upon Scotland’s agricultural revolution, c.1770-1830. Or even more succinctly that it was built with the proceeds of Caribbean slavery. There is no requirement for local heritage organizations to acknowledge the provenance of wealth that transformed the Scottish estates that are now country parks. However, as the imperial wealth that helped, in part, improve vast swathes of Scotland’s built heritage becomes increasingly well known, fresh questions will be raised how this is interpreted. Mugdock park is currently an exemplar of the silences of Scotland and Caribbean slavery.

The Glasgow Sugar Aristocracy: Scotland and Caribbean Slavery 1775-1838

For more on the Smiths of Craigend/Jordanhill and their estate acquisition strategies, see The Glasgow Sugar Aristocracy: Scotland and Caribbean Slavery, 1775-1838, (University of London Press, 2022) which can be purchased as a book or downloaded free as a pdf here: https://www.sas.ac.uk/publications/glasgow-sugar-aristocracy

References

[1]. J. G. Smith, The Parish of Strathblane and Its Inhabitants from Early Times (Glasgow, 1886), p. 57.

[2]. Measuring Worth. Available: https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/result.php?year_source=1815&amount=71027&year_result=2023

[3]. Smith, Strathblane, pp. 52–7.

[4]. Smith, Strathblane, p. 55.

African Caribbean Cultures Belmont Estate Commemoration Compensation Cotton Emancipation Glasgow Glasgow West India Association historical amnesia Houstons of Jordanhill Imperialism Jacobites James MacQueen Kingston landed estates merchant house Museums plantation Port Glasgow Presbyterianism Public history Research Robert Burns Scots and Empire YouGov Scots Kirk Slavery Smiths of Jordanhill Sugar the West Indies Victimology

On 17 November, Tom Devine wrote an

On 17 November, Tom Devine wrote an  David Livingstone was born in Blantyre Mill in 1813. The mill was taken over by Henry Monteith in 1802, manufacturer, Tory politican and Lord Provost of Glasgow twice in the 1810s. Monteith was in partnership with three separate merchants in Glasgow who owned shares in West India firms: Adam Bogle, Alexander Garden and Francis Garden. These partnerships with colonial merchants brought capital derived from slavery into the business and the cotton to supply the mill. The overall investments by West India merchants in cotton manufactories seem to have been relatively small, but it behoves us to remember where the cotton was grown. And the bulk of Blantyre’s exports went to Africa. But work in Blantyre Mill was both arduous and dangerous. In 1823, Livingstone was put to work aged ten as a ‘piecer’ and was part of a child labour force. Ten years later, James Stuart visited Blantyre Works and was scathing about working conditions. There is no question the elites profited from a double-level of transatlantic exploitation: that of the enslaved people in the West Indies and the Scottish labourers. Yet, the conditions of both cannot be compared. In Blantyre Works, housing and educational facilities were noted to be of a high standard. Monteith was known as a paternalist owner, and in fact Livingstone defended cotton masters in a speech on his return to the Mill in 1856. Crucially, the work in Blantyre Mill was well-paid. In 1832, the wage rate for mill-workers was tenth highest (from twenty-nine) cotton mills in the Glasgow area. Moreover, the wages on offer were more than was available to weavers in the twenty weaving mills in the local area. The high wages on offer at Blantyre partly explain why ‘lad of pairts’ Livingstone was able to save and invest five months of his income into a medical education at the Andersonian and Old College (now Glasgow University). By his own admission – Livingstone was well-paid for work in a cotton mill owned by a conglomerate of West India merchants. And he was part of a major textile labour force in Scotland. As historian Anthony Cooke has shown, textile manufacturers were the largest employers in Scotland (cotton 154,000 of 257,900 (60%), linen 30%, and wool 10%). Citing Sir John Sinclair in 1826, the cotton industry in particular was ‘by far the most important in the kingdom in regard to both the number of persons employed and to the value of their labour’ [3].

David Livingstone was born in Blantyre Mill in 1813. The mill was taken over by Henry Monteith in 1802, manufacturer, Tory politican and Lord Provost of Glasgow twice in the 1810s. Monteith was in partnership with three separate merchants in Glasgow who owned shares in West India firms: Adam Bogle, Alexander Garden and Francis Garden. These partnerships with colonial merchants brought capital derived from slavery into the business and the cotton to supply the mill. The overall investments by West India merchants in cotton manufactories seem to have been relatively small, but it behoves us to remember where the cotton was grown. And the bulk of Blantyre’s exports went to Africa. But work in Blantyre Mill was both arduous and dangerous. In 1823, Livingstone was put to work aged ten as a ‘piecer’ and was part of a child labour force. Ten years later, James Stuart visited Blantyre Works and was scathing about working conditions. There is no question the elites profited from a double-level of transatlantic exploitation: that of the enslaved people in the West Indies and the Scottish labourers. Yet, the conditions of both cannot be compared. In Blantyre Works, housing and educational facilities were noted to be of a high standard. Monteith was known as a paternalist owner, and in fact Livingstone defended cotton masters in a speech on his return to the Mill in 1856. Crucially, the work in Blantyre Mill was well-paid. In 1832, the wage rate for mill-workers was tenth highest (from twenty-nine) cotton mills in the Glasgow area. Moreover, the wages on offer were more than was available to weavers in the twenty weaving mills in the local area. The high wages on offer at Blantyre partly explain why ‘lad of pairts’ Livingstone was able to save and invest five months of his income into a medical education at the Andersonian and Old College (now Glasgow University). By his own admission – Livingstone was well-paid for work in a cotton mill owned by a conglomerate of West India merchants. And he was part of a major textile labour force in Scotland. As historian Anthony Cooke has shown, textile manufacturers were the largest employers in Scotland (cotton 154,000 of 257,900 (60%), linen 30%, and wool 10%). Citing Sir John Sinclair in 1826, the cotton industry in particular was ‘by far the most important in the kingdom in regard to both the number of persons employed and to the value of their labour’ [3].

gar, 1783-1838. Smith’s firm, Leitch & Smith, was one of the most extensive firms of its type in Glasgow in the period, importing sugar and providing credit to slave-owners in the south-eastern Caribbean island of Grenada as well as Jamaica. John Guthrie managed Leitch & Smith’s sister firm on Grenada in the late 18th century. Guthrie & Ryburn was established sometime after 1792 and became the largest firm on the island. By 1799, Guthrie was a respected member of the plantocracy elite on the island, and was appointed a ‘Guardians of Slaves’ in the capital St George’s. A fortune based on slavery secured, John Guthrie returned to Scotland after around a decade in Grenada [1].

gar, 1783-1838. Smith’s firm, Leitch & Smith, was one of the most extensive firms of its type in Glasgow in the period, importing sugar and providing credit to slave-owners in the south-eastern Caribbean island of Grenada as well as Jamaica. John Guthrie managed Leitch & Smith’s sister firm on Grenada in the late 18th century. Guthrie & Ryburn was established sometime after 1792 and became the largest firm on the island. By 1799, Guthrie was a respected member of the plantocracy elite on the island, and was appointed a ‘Guardians of Slaves’ in the capital St George’s. A fortune based on slavery secured, John Guthrie returned to Scotland after around a decade in Grenada [1]. The landed estate was not only a solid investment, but the title improved Guthrie’s social standing. In Glasgow, he was appointed a city magistrate in 1810-1811. He was Dean of Guild of the Merchants House in 1814 (an influential position in local politics). On his death in 1834, Guthrie was worth £8977, not a huge fortune by the standards of the Glasgow West India elite, but a sum that would have placed him comfortably in the ranks of the developing middle-class in Scotland [3].

The landed estate was not only a solid investment, but the title improved Guthrie’s social standing. In Glasgow, he was appointed a city magistrate in 1810-1811. He was Dean of Guild of the Merchants House in 1814 (an influential position in local politics). On his death in 1834, Guthrie was worth £8977, not a huge fortune by the standards of the Glasgow West India elite, but a sum that would have placed him comfortably in the ranks of the developing middle-class in Scotland [3].